Atomicity

“But is this database atomic?”

This is the most common scenario when someone would remember atomicity. However, this is one of the core concepts which is incredibly useful when implementing fault-tolerant systems. It’s good to keep it handy and use when reviewing pull requests. In some cases, it might also be very hard to plan ahead.

What is atomicity?

Atom is a definition of the smallest indivisible particle. An atomic operation should perform as a whole or not perform at all.

Why this is useful?

In the real world, things tend to fail most unpredictably. Both software and hardware can fail. If you have dependencies to 3rd party services - or utilise the network in any capacity - that can of course fail. When you are persisting data to a local file or a remote bucket, or reading/writing to a database - any of those operations can fail.

It’s generally a good idea to fail predictably, with good logs, alerts and least effect to end-users. It’s also nice to have an option to recover from failure. This is not always possible. But when you are limiting ways how a system could fail, recovery becomes a much easier task.

The atomic approach is especially useful when you are implementing jobs processing large batches of data. In this case, you are risking thousands (if not millions) corrupted records when something fails.

Example

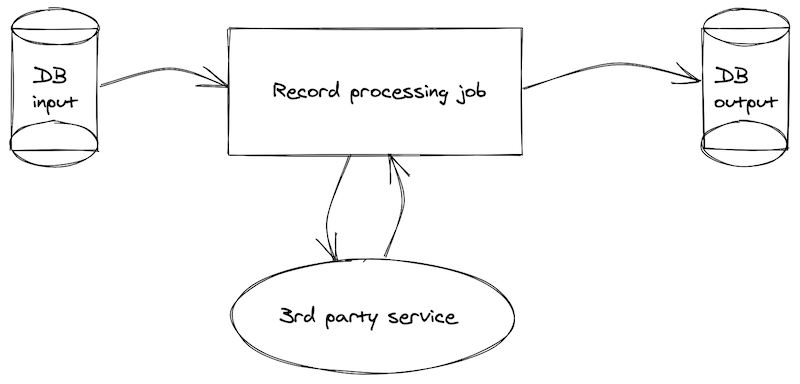

Let’s say we have a job that validates and processes records in a database. Each record is read, validated using a 3rd party, and then written to 2 different tables depending on the result of that validation. We also mark each original record as “read” so that we could skip it from processing next time.

Our pseudocode would look something like this:

originalRecords = readFromDb()

markAsRead(originalRecords)

[validRecords, invalidRecords] = validateWith3rdParty(originalRecords)

writeToTableA(validRecords)

writeToTableB(invalidRecords)

Technically there is nothing wrong with this implementation. It will be fine in most cases. We can have proper logging and alerts around it.

However, when that 3rd party service goes down, we will find ourselves in a heap of trouble. Not only we will fail to perform the operation, but also by the time of the fail, a record currently being processes is already marked as “read” on the original record. This means it will fail to process, and will be skipped the next time this job runs.

Even worst - all of the records in the original batch are already (quite optimistically) marked as “read” - meaning the whole batch would not be retried next time when a 3rd party service might be back up.

Identifying weak links

Anything can fail, but the likelihood will vary. It is safe to assume that any 3rd party service could go down at any moment, and your service should be able to recover from this. It is also not productive to expect anything to fail at any moment.

Personal top of things that are likely to fail:

- 3rd party services

- Our services that rely on 3rd party services

- Unexpected input data

- Data persistence (database or a cloud bucket)

- Data read from a database

Things are more likely to fail under an increased load or with a significantly larger batch size than you would usually expect.

Improving atomicity

Batch processing is a good concept for fault tolerance. When a given batch fails, you can restart and try again. In this example, we could be even more granular and implement an atomic operation on a record level.

An improved implementation could look something like this.

originalRecords = readFromDb()

originalRecords.forEach(record => {

validationResult = validateWith3rdParty(record)

markAsRead(record)

if (validationResult)

writeToTableA(record)

else

writeToTableB(record)

})

This way we are processing one record at a time. We have also moved a call to the 3rd part service to the very top. This way if it fails, nothing else will be executed. A record would not be marked as read, which means next time when this job runs, it will be automatically retried.

Can we improve this even further? Yes - we could move markAsRead() to the very bottom of the loop. This way we are making sure that a record is marked as read only when all of the operations are successful. A nice atomic approach.

More thinking

Atomicity is a concept, but you can apply it in any situation when a state of a system is involved. It will allow you to gracefully recover from failures and have a more predictable state of your system. Which is good, because the code we write makes a lot of assumptions about the environment.

NASA likes to say that failure is not an option. For the rest of us, failure has to be an option, but it should happen predictably when we can keep the rest of the system from breaking, and be able to easily recover.